Based on published source code and conversations with the woman behind the Parler dump (donk_enby on Twitter), I can completely explain how the Parler data was acquired, and why it was legal. The story making the rounds on Reddit claiming that she somehow hacked Parler and got admin access is third-hand bad techno-madlibs fiction. What she actually did was reverse-engineer the protocol (API) used by the Parler iOS app to communicate with the website backend.

An Application Programming Programming Interface (API) is the way services and websites allow other apps and websites to interact with it. For example, Twitter has an API that allows users to use other services like marketing platforms to manage their Tweets. Likewise, Facebook has an API that lets advertisers manage their campaigns. APIs are also used by mobile apps to interact with the backend services that power the platforms they use. Nowadays, most APIs are built on HTTPS, the same protocol that’s used to securely access websites. APIs can be public (allowing anyone to interact with them), semi-public (allowing only registered users), private (access requires specific credentials), or a combination where different actions are protected at different levels.

By examining the Parler iOS app, donk_enby discovered that the Parler API allowed anyone with a Parler account to view raw post data, including posts that were deleted by their authors. When a user deleted a post (known as a parlay), the website wouldn’t actually delete the content. Instead, it would flag the post as deleted in the backend. The website and apps would hide these “deleted” posts. This kind of soft-delete is a common best-practice on many social media sites, so that even if a user deletes a post, those in charge of running the site can review deleted content for violations of website policies. Unlike other social media platforms, Parlor made huge architectural mistakes. When any user queried the API for a list of posts, the API returned all posts, both published and deleted. Standard best-practice development is to hide restricted content from those who are not authorized to see it, no matter what method of used to access the content, including APIs. Instead, Parler’s developers relied on the website or app UI to not display the posts the API indicated were “deleted”. This lack of Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) in the API led to a sensitive information exposure vulnerability. The API did not put a limit on the number of queries that could be executed in a given time frame, allowing anyone to retrieve information at a rapid pace.

Parler’s shoddy design allowed any Parler user account to access all of this information via an undocumented API without bypassing or breaking any security controls. The proper security controls were simply not implemented by Parler’s developers in the first place.

Static files such as photos and videos were stored in an Amazon S3 bucket with a sequential naming convention that made the files easy to enumerate. This content and the URLs linking to them remained active even after a user soft-deleted their post. Parler further exposed user information by not stripping the metadata in user’s uploaded media files before hosting them, including GPS location coordinates that a frequently added by smartphones when taking photos or videos.

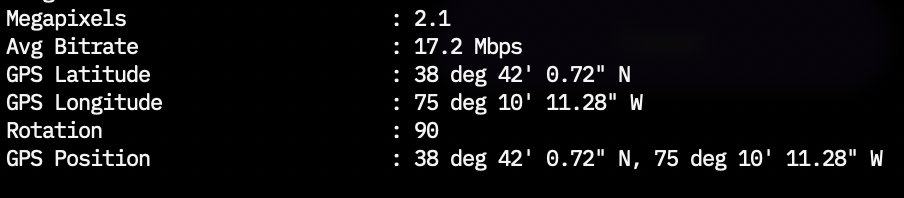

The metadata in these files can easily be viewed using a free tool like exiftool, such as in this screenshot posted by donk_enby.

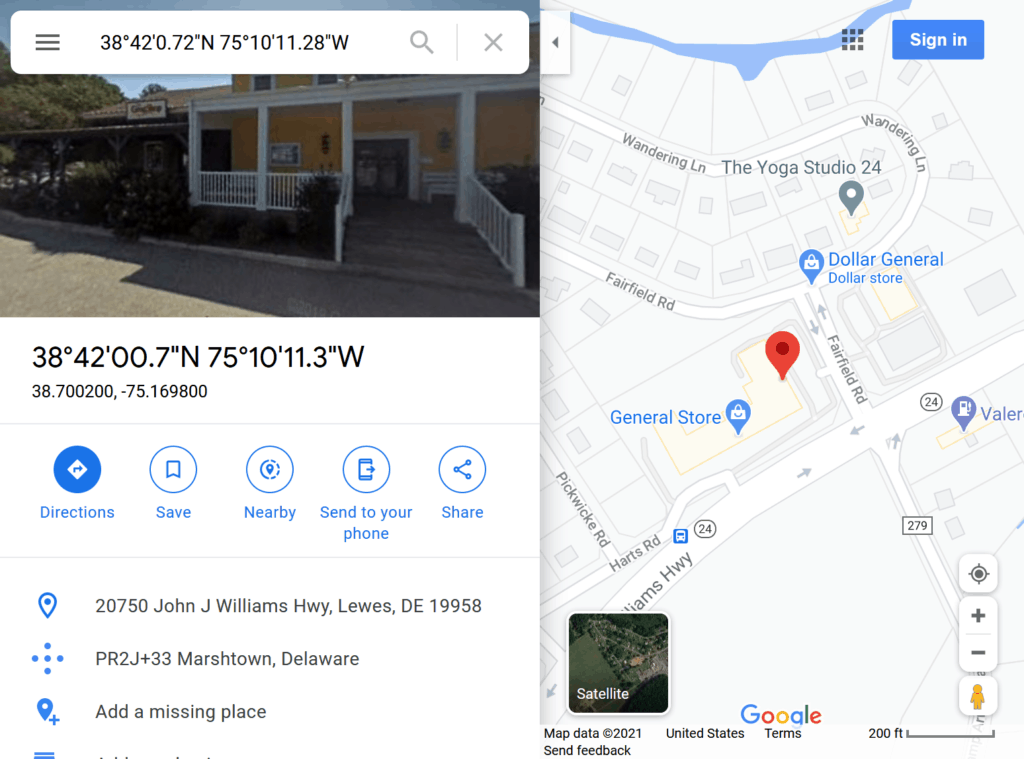

Using Google Maps, it is an easy task to convert those coordinates, showing that this particular video was recorded at a location inside the General Store in Marshtown, Delaware.

Retrieving this information is not illegal. In a textbook case of security through obscurity, Parler’s shoddy design allowed any Parler user account to access all of this information via an undocumented API without bypassing or breaking any security controls. The proper security controls were simply not implemented by Parler’s developers in the first place.

donk_enby wrote Python scripts that leverage Parler’s API just like the iOS app would. She shared the scripts on GitHub on December 7th, 2020, in a cleverly-named repository called parler-tricks.

In the README file, she notes:

Use it to solve fun mysteries such as:

- Is my dad on Parler?

- Who was on Parler before it first started gaining popularity when Candice Owens tweeted about in December 2018?

- Which users have administration and moderation rights? (hint:

(interactions >> 5) & 1= moderator,(interactions >> 6) & 1= admin) - What exactly is an “integration partner”, and which media entities currently are they?

- If Parler is really yet to come up with a business model for how to make money, then what exactly is a Campaign Promoter Management Network?

She also sites a section of the DCMA that protects her from DCMA violation claims resulting from publishing the scripts.

Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) USC § 1201 (f) states:

A person who has lawfully obtained the right to use a copy of a computer program may circumvent a technological measure that effectively controls access to a particular portion of that program for the sole purpose of identifying and analyzing those elements of the program that are necessary to achieve interoperability of an independently created computer program with other programs, and that have not previously been readily available to the person engaging in the circumvention, to the extent any such acts of identification and analysis do not constitute infringement under this title.

In the wake of the US Capital riots that were organized in part by Parler users, Amazon gave Parler 24 hours notice that it would stop providing hosting services, for failing to consistently remove calls for violence in a timely manner for years. Researchers and activists used donk_enby’s scripts to quickly archive nearly all of Parler’s content — 30 TB in size — before Amazon took the website down.

Location data from photos and videos of the riots allowed Gizmodo to pinpoint how disturbingly far rioters advanced inside the Capital. This data will clearly make the FBI’s task of identifying rioters and those inciting violence much, much easier.

Archiveteam and Archive.org (unrelated to each other) are each building their own archives of Parler content, which should be public soon.

Even if Parler manages to find a new host for the toxic platform, and adds RBAC and rate-limiting to their API, they cannot remove the API entirely without breaking the mobile applications for those who would still use them — potentially reducing their userbase in the process.

Parler users seem to be moving to Gab, another upstart social media platform full of disinformation and anger, but one that is much better built.

Update: Ironically, shortly after the above statement was posted, Gab was the victim of a data breach. Parler has since come back one line, and briefly blocked its ex-CEO. Apparently, fascists aren’t good at AppSec.

Great article – thanks for sharing this~!

Capt. Greg

Hello,

I’m an old guy retired programmer. I have screen scraping skills. Is there anyway I can join the team?

[email protected]

I’m not a part of the team that id doing this, but you might want to reach out to the archive.org project.