How to install YARA and write basic YARA rules to identify malware

A complete YARA guide, covering installation, practical examples for writing YARA rules, and using YARA to identify, sort, and collect malware samples

YARA is described as “The pattern matching Swiss knife for malware researchers (and everyone else)”. Think of it as like grep, but instead of matching based on one pattern, YARA matches based on a set of rules, with each rule capable of containing multiple patterns, and complex condition logic for further refining matches. It’s a very useful tool. Let’s go over some practical examples of how to use it.

Installing YARA

Official Windows binaries can be found here. Unfortunately, as of the time of this writing, practically every Linux distribution’s repository contains an out-of-date version of YARA that has one or more security vulnerabilities. Follow the instructions below to compile and install the latest release with all features enabled on a Debian or Ubuntu system. The steps should be similar in other Linux distributions.

Download the source code .tar.gz for the latest stable release.

Install the dependencies

1

sudo apt-get install -y automake libtool make gcc flex bison libssl-dev libjansson-dev libmagic-dev

Build the project

1

2

3

4

5

6

tar -zxf v3.9.0.tar.gz

rm v3.9.0

cd yara-3.9.0

./bootstrap.sh

./configure --with-crypto --enable-profiling --enable-macho --enable-dex --enable-cuckoo --enable-magic --enable-dotnet

make

Install as a Debian package

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

sudo apt-get install -y checkinstall

sudo apt-get remove -y libyara3 yara python-yara # Remove any existing install from distro repos

sudo checkinstall -y --deldoc=yes

# Cleanup

cd ..

rm -rf yara-3.9.0/

Install the Python package

1

2

3

4

5

sudo apt-get install -y python-pip python3-pip

sudo -H pip install -U pip

sudo -H pip3 install -U pip

sudo -H pip install -U git+https://github.com/VirusTotal/yara-python@3.9.0

sudo -H pip3 install -U git+https://github.com/VirusTotal/yara-python@3.9.0

Introduction to YARA rules

Let’s start by looking at the different components that can be part of a rule.

At a minimum, a rule must have a name, and a condition. The simplest possible rule is:

1

rule dummy { condition: false }

That rule does nothing. Inversely, this rule matches on anything:

1

rule dummy { condition: true }

Here’s a slightly more useful example that will match on any file over 500 KB:

1

rule over_500kb {condition: filesize > 500KB}

Most often though, you’ll write rules with a meta section, a strings section, and a condition section:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

rule silent_banker : banker {

meta:

description = "This is just an example"

threat_level = 3

in_the_wild = true

strings:

$a = {6A 40 68 00 30 00 00 6A 14 8D 91}

$b = {8D 4D B0 2B C1 83 C0 27 99 6A 4E 59 F7 F9}

$c = "UVODFRYSIHLNWPEJXQZAKCBGMT"

condition:

all of them

}

The : after the rule name indicates the start of a list of rule tags, which are separated by spaces. These tags are not used frequently, but you should be aware that they exist. C-style comments can be used anywhere.

The meta section consists of a set of arbitrary key-value pairs that can be used to describe the rule, and/or the type of content that it matches. Meta values can be strings, integers, decimals, or booleans. The meta values can be viewed by the application that is using YARA when a match occurs.

The strings section defines variables as content to be matched. These can be:

- Hexadecimal byte patterns (in

{}, with support for wildcards and jumps). Often used to identify unique code, such as an unpacking mechanism - Text strings

- Regular expressions (between

//)

The condition section is where the true power an flexibility of YARA can be found. Here are a few common example condition statements

| Condition | Meaning |

|---|---|

any of them | The rule will match on anything containing any of the strings defined in the rule |

all of them | The rule will only match if all of the defined strings are in the content |

3 of them | The rule will match anything containing at least three of the defined strings |

$a and 3 of ($s*) | Match content that contains string $a and at least three strings whose variable begins with $s |

Practical examples

It would be very useful to check the attachments of suspected phishing emails reported to you by your users. PDF attachments with a link to a phishing site have become a common tactic, because many email gateways still do not check URLs in attached files. This rule checks for links in PDFs:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

rule pdf_1.7_contains_link {

meta:

author = "Sean Whalen"

last_updated = "2017-06-08"

tlp = "white"

category = "informational"

confidence = "high"

description = "A PDFv1.7 that contains a link or external content"

strings:

$pdf_magic = {25 50 44 46}

$s_anchor_tag = "<a " ascii wide nocase

$s_uri = /\(http.+\)/ ascii wide nocase

condition:

$pdf_magic at 0 and any of ($s*)

}

The first part of the condition checks if the first few bytes of the file match the magic numbers (list here) for a PDF, allowing the rule to quickly disregard anything that isn’t a PDF. Filters like these can greatly increase speed when scanning a large amount of data. The second part of the condition strings whose variable begins with $s.

$s_uri is a regular expression that matches any URI/URL in parenthesis, which will match the PDF standard for URI actions and URLs in forms.

$s_anchor_tag matches any HTML anchor tag, which some PDF converters may leave an a document converted from HTML.

The ascii, wide , and nocase keywords tell YARA to search for ASCII and wide strings, and to be case-insensitive. By default, it will only search for ASCII strings, including substrings, and it will be case-sensitive. There are many more keywords for matching other kinds of strings.

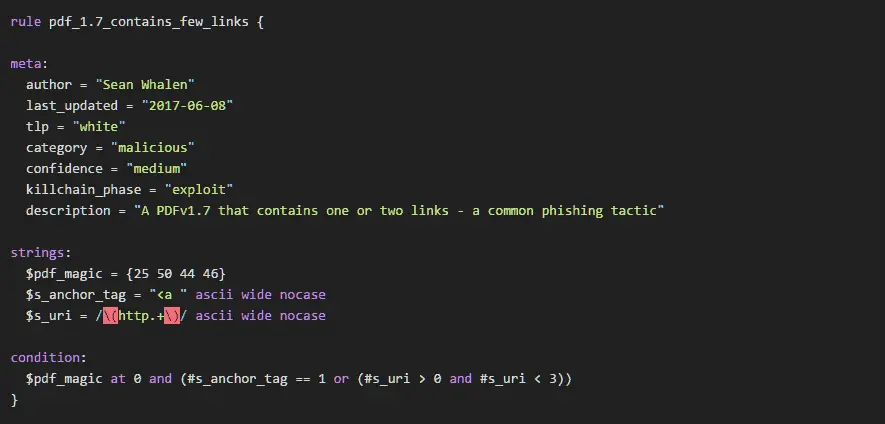

But lots of legitimate PDFs (brochures, invoices, etc) contain links, so a better indicator of badness may be a PDF that contains a single link. Unfortunately, most PDF generators like Microsoft Office will save the PDF as multiple “versions” in the same file, so we should give the rule a little flexibility, and allow for up to two URIs in a PDF.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

rule pdf_1.7_contains_few_links {

meta:

author = "Sean Whalen"

last_updated = "2017-06-08"

tlp = "white"

category = "malicious"

confidence = "medium"

killchain_phase = "exploit"

description = "A PDFv1.7 that contains one or two links - a common phishing tactic"

strings:

$pdf_magic = {25 50 44 46}

$s_anchor_tag = "<a " ascii wide nocase

$s_uri = /\(http.+\)/ ascii wide nocase

condition:

$pdf_magic at 0 and (#s_anchor_tag == 1 or (#s_uri > 0 and #s_uri < 3))

}

It’s good to keep both of these rules, that way you have an informational one that should always match on any PDF with any number of links, and another that provides a higher confidence of badness.

Also, these rules only match PDFs with links that were generated according to the latest PDF standard (1.7). Any suggestions for older versions are appreciated.

Viewing strings in a file

To view a list of strings in a file, simply run the strings command on a Linux/MacOS/BSD or other UNIX-like system. You can pipe the output to less to view it one page at a time. For example:

1

strings rat.exe | less

Strings vs Bytes

the strings section in YARA rules can be made up of any combination of strings, bytes, and regular expressions. Most YARA rules are made up entirely of strings. These kinds of rules are relatively simple to write, but it is also very easy for malware authors to change or obscure strings in order to avoid detection in future builds. If a sample has few or no usable strings, that sample has likely been packed, meaning that any strings are built or decoded at runtime. YARA can scan processes, and you probably would have better luck scanning active memory for strings, but that won’t help if your goal is to identify samples at rest.

Bytes in YARA are represented as hexadecimal strings, and can include wildcards and/or jumps. Bytes can be used to identify specific variations of code, such as a unique method of unpacking. Writing signatures based on bytes requires some knowledge of assembly, APIs provided by the OS, and specialized software.

IDA Pro is the industry standard platform for software reverse engineering. It is also very expensive. Currently, a the Starter Edition of IDA (which can only process 32 bit files) for one named user, along with the X86 Hex-Rays decompiler costs about $2,700. If you want to be able to decompile x86 AMD64 files, the cost is about $4,400 for IDA Pro, x86, and x64 compilers for one named user. Fortunately, a couple open source alternatives exist.

In early 2019, the NSA released an open source Software Reverse Engineering (SRE) suite called Ghidra. It includes a decomplier, and a very similar feel to IDA.

The open source Radare Framework provides many of the same features of IDA (and a few more) for free, under a GNU GPL license. Radare does not currently have a decomplier though.

If you’re new to assembly, check out this Crash Course in x86 Assembly for Reverse Engineers.

Testing YARA rules

To test your rules against some sample files, run a command like this:

1

yara -rs dev/yararules/files.yar samples/pdf

Where dev/yararules/files.yar is the path to the file containing your rules and samples/pdf is the path to a directory containing sample files to test against. This will output a list of files matches, and the strings that make up each match.

To find samples that do not match your rules, run a command like this:

1

yara -rn dev/yararules/files.yar samples/pdf

Note that this will give a a result for each rule that each file does not match. Use grep to narrow this down. For example, if you only wanted to see the results for rules with a name that contains pdf_, you could run:

1

yara -rs dev/yararules/files.yar samples/pdf | grep pdf_

It’s good practice to keep your rule names consistent. That makes testing much easier.

Generating rules

yarGen is an open source utility by Florian Roth that generates YARA rules for a given set of samples. It’s not magic, and generally won’t do a better than writing a rule manually. But, if you are mostly making rules out of strings rather than bytes, it can give you a great starting point to tweak and tune into a better rule. I use yarGen when I’ve some across a set of samples that I know are related, but have seemingly very different strings.

yarGen will generate many different rules for a given set of files, and the condition for each rule will likely be very narrow (i.e. all of them). I usually combine these rules based on what I suspect are the most reliable strings, and group the strings as needed in the condition statement.

You can download yarGen from its GitHub repository.

Learning more

Take some time to review the comprehensive official documentation for YARA. There, you will find complete details on writing rules, and using the command-line program, the Python API, and the C API.

Once you feel comfortable working with YARA, consider joining the YARA Exchange. The Exchange is a very active and helpful group of information security professionals that share rules and tips for writing them. You can even get access to VirusTotal Intelligence for free through the exchange, if your company doesn’t already pay for it. In return, they only ask that you participate, share with others, and don’t hog the VirusTotal Intelligence monthly quotas that are shared across the whole group.

With VirusTotal Intelligence access, you can set up alerts to notify you when samples are uploaded to VirusTotal that match your YARA rules, without using any quotas. It’s a fantastic way to stress test your rules (your inbox/alert queue will fill up very quickly if you match false-positives), and for identifying new samples, and new waves of attacks. Quotas are used for searching, downloading, and using Retro Hunt on VirusTotal Intelligence. Retro Hunt takes a set of YARA rules, runs a scan on about the last three months of all files that were uploaded to VirusTotal (literally terabytes of data), and returns a list of file hashes that matched your rules, and which rules they matched.

Check out this great talk on getting the most out of VirusTotal Intelligence and YARA by Wyatt Roersma at GrrCon 2016:

Books

Other resources

- Public rule repository

- YARA for Visual Studio Code

- Atom editor package for YARA syntax highlighting