WannaCry ransomware analysis: Samples date back to at least early February 2017

Information on the spread, mitigation, and patch details of WannaCry, The ransomware that has shut down organizations around the world.

The WannaCry ransomware worm has spread panic and destruction as it infects hundreds of thousands of systems around the world; a rate not seen since the Blaster and Sasser worms of

- WannaCry – also known as WannaCrypt, WannaCryptor, WanaCrypt0r, WCry, or WCrypt – leverages vulnerabilities that Microsoft patched in the March MS17-010 Security Bulletin, after taking the unprecedented step of canceling the February Patch Tuesday.

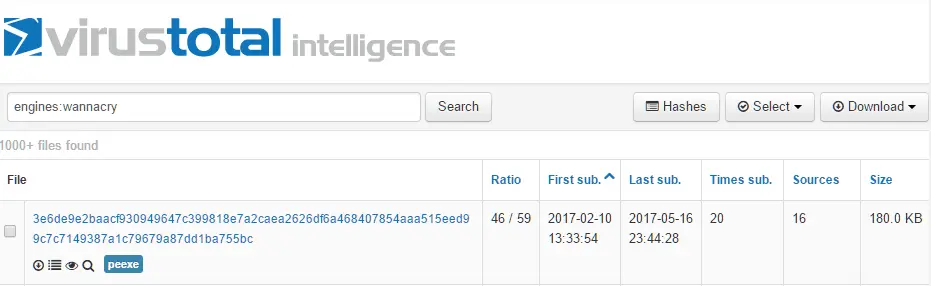

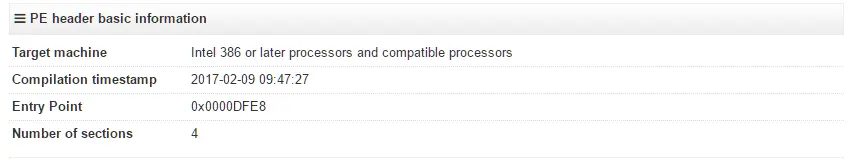

While collecting samples of WannaCry, I found a sample that predates the worm version. The sample was compiled on February 9th, and uploaded to VirusTotal on February 10th. While compile timestamps can be faked, the closeness to the upload date suggests that the compilation timestamp is legitimate.

Malware authors will often upload their builds to VirusTotal as a lazy way of testing against current versions of almost all anti-malware products, before using the malware against their targets. VirusTotal allows security professionals to search and download these samples through their paid VirusTotal Intelligence subscription.

Through this service, I found that when the February sample was first uploaded, only three anti-malware products detected the sample as malicious, though only with generic/heuristic signatures. By March 12th, most major anti- malware products detected this sample as some form of ransomware – some mistook it as a Locky variant. When WannaCry 2.0 began spreading as a worm on May the 12th, the attackers had adjusted the malware so that only a few products detected these new samples as malicious.

Fortunately, WannaCry samples to date have not been packed or otherwise obfuscated. A few days after the initial worm outbreak, almost every anti- malware software was updated in ways that detect all known variants of WannaCry, but not before the ransomware disrupted hospital care across the UK, and paralyzed hundreds of other organizations worldwide. Of course, the attackers will eventually make changes to avoid detection again. This is a typical detection pattern for new malware, which illustrates why any one product – including “next gen” products – should not be relied upon on its own to keep a network safe.

A hacking group known as the Shadow Brokers reportedly stole a large cache of weapons-grade exploits, tools, and data from the NSA. Microsoft released a patch for some of those exploits a month before they were publicly released by the Shadow Brokers, leaving many to speculate that Microsoft was tipped off by the NSA. A month after the public Shadow Brokers dump, the authors of WannaCry incorporated a SMB exploit from the dump to turn WannaCry into the most widespread worm in over a decade.

This whole situation shows not only how dangerous widespread software vulnerabilities can be, but how information security defenses and procedures are fundamentally insufficient in many organizations. Those who were affected by the WannaCry ransomware worm were at least two months behind on software patches rated by Microsoft as critical.

Timeline

- 2017-02-10 – First known sample of WannaCry is uploaded to VirusTotal

- 2017-02-17 – Microsoft cancels patch Tuesday

- 2017-03-14 – Microsoft posts the MS17-010 Critical Security Bulletin and patches, including one for a SMB flaw

- 2017-04-14 – The Shadow Brokers leak multiple exploits reportedly stolen from the NSA, including one that exploits the SMB flaw patched in MS17-010

- 2017-05-12 – WannaCry 2.0 begins spreading as a worm by using the SMB exploit

- 2017-05-12 – Microsoft releases customer guidance for WannaCry and emergency patches for unsupported versions of Windows, including Windows XP and Windows Server 2003.

- 2017-05-16 – The Shadow Brokers announce a “subscription service” coming in June for receiving future data leaks, and claim to have 75% of the U.S. cyber arsenal

Despite the availability of patches and updated anti-malware signatures, ransom money continues to flow to the attackers throughout the day. There are three known Bitcoin wallet addresses where victims are directed to send ransom payments:

- 115p7UMMngoj1pMvkpHijcRdfJNXj6LrLn

- 12t9YDPgwueZ9NyMgw519p7AA8isjr6SMw

- 13AM4VW2dhxYgXeQepoHkHSQuy6NgaEb94

At the time of this writing, these wallets combined have received a total of 46.30 Bitcoin, which is worth about $86,447.80 based on a 24-hour average exchange rate of 1 BTC ≈ $1,867.01 USD. The ransom amounts range from $300-$600 per system.

Reports indicate that North Korea may be using WannaCry to fund its weapons programs as it faces tightening international sanctions and isolation.

The kill switch implementation is odd

In some ways, having a kill switch for a worm makes sense. If something horribly unexpected happens with your code – e.g. it crashes a system 50% of the time – you may want to kill the worm before it can brick half of your potential targets. What’s odd about WannaCry’s kill switch is that it simply checked for the registration of a predetermined domain name, which lead one researcher to register it, not knowing it was a kill switch. It stopped the worm in its tracks, until the attackers launched a version without a kill switch. These seem like lazy development choices. WannaCry was already using asymmetric encryption; why not use that to verify the kill switch server?

Speculation on WannaCry’s initial infection vector

One of the remaining questions around WannaCry is: How do the attackers initially get the malware to run on a system in a network? There was some initial speculation in the information security community that a phishing campaign was employed. However, days after the malware outbreak, a phishing lure has not been identified, making such a scenario increasingly unlikely.

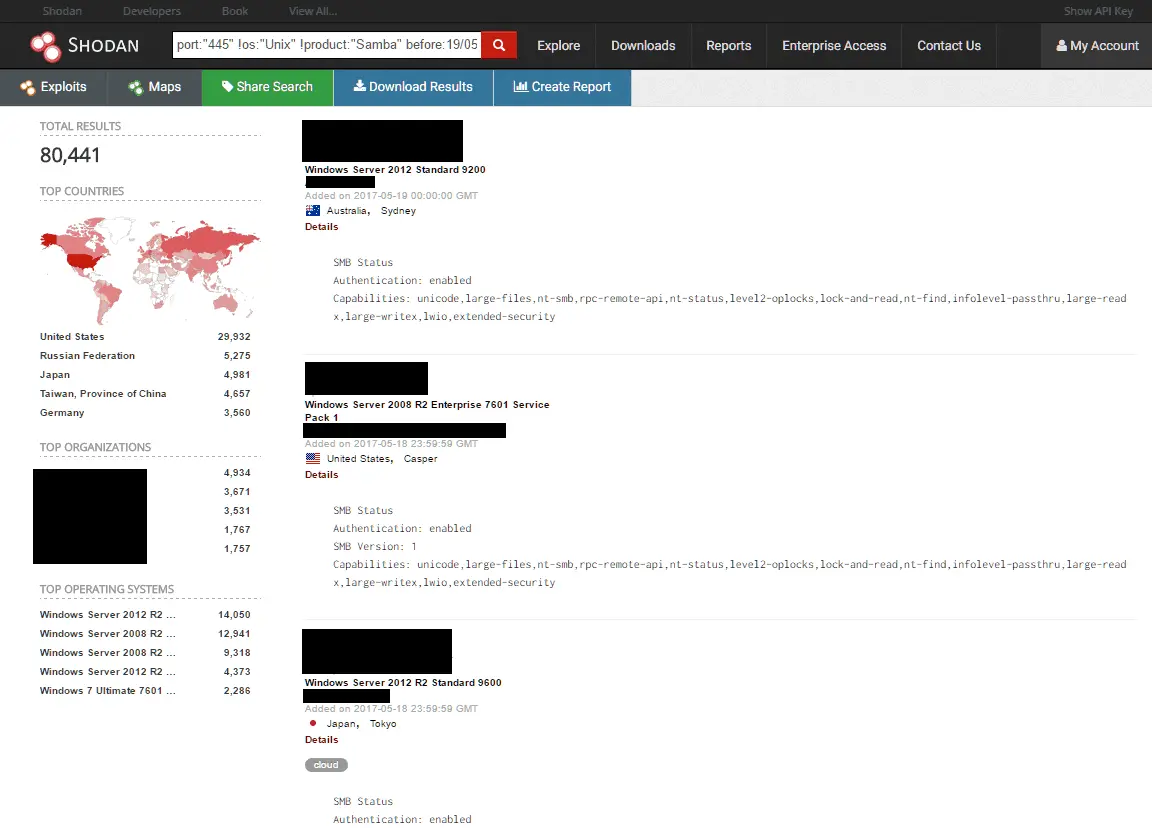

The vulnerable protocol exploited by WannaCry is SMB, which is mainly used to share files and administer systems on a local network. While most networks block outside SMB traffic, a quick search of Shodan (It’s like Google, but it indexes services exposed to the internet. not web pages) reveals that there are at least 80,441 Windows systems with SMB services exposed to the internet, a good number of which are bound to be unpatched. The number varies from day to day. Although this number has likely decreased somewhat from when WannaCry 2.0 was first released, as organizations mitigate the worm threat, it would only require one vulnerable server to gain access to a network. From there, it would be trivial to pivot to other systems on the LAN.

Lessons from WannaCry

- Patch early, patch often

- Monitor and restrict services open to the internet

- Create regular out-of-band backups, and test restoration

Also check out my ransomware defense-in-depth guide.

Note: A previous version of this article referenced 1,202,995 Shodan results for Windows systems with exposed SMB. I have since learned that number included past results, and was therefore inaccurate. The new results are filtered to only include services that were active on 2017-05-18, the original publication date of this article.